Roadmaps to a Resilient Society

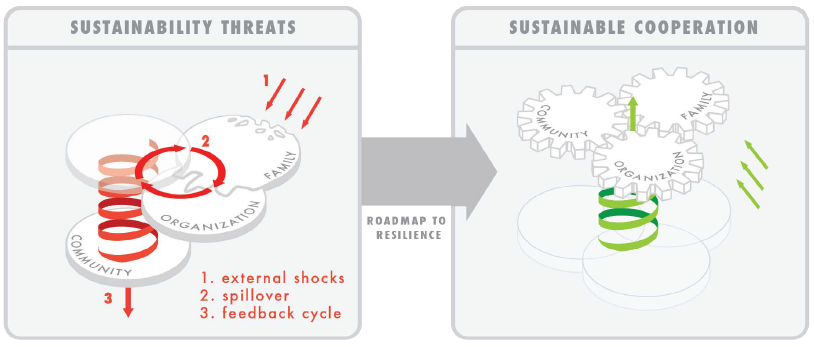

Resilient societies are able to maintain high levels of care, work, and inclusion, despite the challenges posed by changing circumstances. We argue that a key component in the potential of societies to achieve this resilience is their ability to sustain cooperation within and between families, organizations, and communities.

Three Kinds of Sustainability Threats:

Cooperation is difficult to sustain over time. Cooperation in one area (in organizations) can undermine it in another (the family). There can be undesirable consequences, for instance for individuals not involved, and the conditions on which cooperation was established can change. Even though cooperation is a fundamental and inextricable part of the human condition, it is not surprising that the journal Science in 2005 placed it atop its list of the most compelling scientific puzzles to be solved. The SCOOP consortium proposes a major, interdisciplinary multi-methods program of study to identify the secrets of sustainable cooperation and elucidate its effects on care, work, and inclusion.

Threats from External Shocks: From Coping to Thriving

External shocks are events originating outside the three group-level domains (families, communities, and organizations), and affect their cooperation and value creation. Such exogenous processes can have their sources in the natural, technical, or institutional environment, like natural hazards or technical inventions, but also in large-scale institutional reform (e.g. decentralization), violent conflicts, or mass migration. Furthermore, though many external shocks may manifest themselves as sudden events, they may nevertheless be the result of chronic cumulative processes. Such disruptions may also function as catalysts toward new and eventually more beneficial cooperative arrangements. However, up to now, it is unclear why this happens, especially where it concerns the contribution of families, communities, and organizations to this resilience, as explicit analyses and empirical tests are scarce. Under what conditions will societies not only successfully cope with external shocks, but also thrive?

In addition to external shocks, cooperation can be subject to self-defeating or self-reinforcing feedback cycles. Cooperation is self-defeating if the arrangements that make it possible also undermine it in the long run. The time frames of such virtuous or vicious cycles can vary, occurring within days or unfolding over centuries, hence the importance of the historical perspective attuned to the role of societal level institutional change. An example of a long-term vicious cycle is the development of the Western European Marriage Pattern: decreasing household size and increasing marriage ages for both men and women led to greater labour market participation of women during the late medieval period. Such demographic changes accelerated economic development in North-western Europe, vis-à-vis the rest of the world, but they also led to weaker family ties.

A classic example of a self-undermining process that unfolds over several years is the vicious cycle of bureaucracy. This emerges when firms impose impersonal rules to resolve cooperation and control problems. In turn, such rules can lower the work motivation of employees, leading to greater intensification of control, ultimately eroding employee commitment further. But cooperation and its outcomes can also result in a virtuous cycle reinforcing the (formal or informal) institutional framework on which they are based. For example, in car factories, workflow interdependencies, which require fine-tuned physical coordination, have been found to reinforce mutual attachment and solidarity between workers. Hence, resilience also crucially depends on how such vicious cycles can be interrupted and even transformed into virtuous cycles of self-reinforcing cooperative arrangements.